Advertise Online

–

SEO - Search Engine Optimization - Search Engine Marketing - SEM

– Domains For Sale

– George Washington Bridge Bike Path and Pedestrian Walkway

– Corona Extra Beer Subliminal Advertising

– Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs

– Pet Care

–

The Tunnel Bar

–

La Cosa Nostra

–

Jersey City Free Books

Historic Houses

The Parsonage

Newark

Where all Newark sought comfort during the dark days of the Revolution

From Historic Houses of New Jersey by W. Jay Mills, 1902

Edited by GET NJ, COPYRIGHT 2002

|

At the corner of Broad and William Streets there formerly stood an old vine-covered building with massive walls and wide window-sills, which perhaps in its day was the best loved and most venerated residence in New Jersey. It is now but a fading memory to the oldest Newark residents, for it was destroyed in 1835, just one century after its erection. Few today remember the stories which cluster about it and form one of the most interesting portions of the history of the old borough.

Into its wide old hall, which echoed to the tread of hundreds of famous people before and during the Revolution, a sad-faced divine in black velvet elegance, leading by the hand a laughing girl in wedding finery, came one bright morning in the long ago, when it was a new dwelling and its history a blank page. They were the Rev. Aaron Burr

and his lady, as we read of them in old records, and to this new home had come on their honeymoon.

Rev. Aaron Burr, at the time of his marriage, was in his thirty-third year, and his bride had just reached nineteen. She was a New Eng land beauty, and is said to have been singularly lovely in both mind and body. She died at the age of twenty-five, outliving her husband one year, and leaving two children, Sarah and Aaron, both born in Newark.

The Rev. Aaron Burr was at that time the president of the infant College of New Jersey. It had been recently removed to Newark from Elizabethtown. His young wife, Esther, fourteen years his junior, was the daughter of the noted Rev. Jonathan Edwards of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, who subsequently, like his distinguished son-in-law, became the head of New Jersey’s seat of learning. Tradition asserts that the marriage created much excitement in the sparsely populated village of that day, and a faint echo of it has lived until the present century in a letter of one of the students of the college, who wrote home to his “mammy” that he could not tell “Mrs. Burr’s qualities and properties, although he had heard she was a very valuable lady.”

|

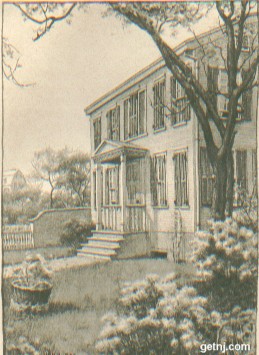

The Parsonage, Newark, In 1800

The Parsonage, Newark, In 1800

|

In one of the second-story rooms of the old house this “valuable lady” became the mother of the famous Aaron Burr, and the happy woman holding him as an infant could never have dreamed of his meteoric career in which misfortune and a degree of greatness were so strangely mingled. The Burrs lived in the Parsonage until the removal of the College of New Jersey to Princetown, in 1756, and its next occupant was David Brainard, a younger brother of the famous missionary Brainard. He seems to have tarried in Newark only a short while. After him came the Rev. Alexander Macwhorter, a young merry-eyed Scotchman, once a student in the college, and then fresh from the tutelage of the Rev. William Tennent, the Monmouth divine who had become famous through his death-trance and journey to heaven, which he vowed had occurred when ill in New Brunswick. While completing his studies at Freehold, under the guidance of the Rev.William Tennent, Alexander Macwhorter met his fate in the person of Mary Cumming, a daughter of a poor but highly respectable merchant of that town.

During the first years of Macwhorter’s pastorate, Newark and the adjoining Elizabethtown, from their nearness to New York City and the Staten Island shore, were the common grounds for foraging parties of both armies. The minister in those thrilling times was a much more important personage in the New Jersey communities than nowadays. As newspapers were scarce, and many of his parishioners had not enjoyed the advantages of the simple course of education then in vogue, he was generally looked to for news of the army. From his high pulpit on Sabbath mornings he cautioned and counseled about worldly as well as spiritual matters, and during the week his house was generally overrun with his flock, ofttimes seeking advice on the most trivial of every-day affairs; in fact, he was the good and benign ruler of the neighborhood.

Many were the timorous ones who hastened to the

Parsonage to be under the sheltering wing of Dominie

Macwhorter’s family when it was noised abroad that the

British were approaching. Under their protection they

felt as secure as they would have been behind the portals of a secret closet, and there was a famous one in Newark in the old Wheeler Mansion, a portion of which is still standing on Mulberry Street. The dominie was seldom at home, for he was a chaplain in the army, and assisted at the council of war which decided on the memorable crossing of the Delaware.

As early as 1775 he visited a district in North Carolina to win over the people in that part of the South unfriendly to the Revolution, and so persuasive was his eloquence that he made many converts.

Newark, in the Revolutionary period, had few houses and inhabitants, yet it was already known as a beautiful and luxuriant county. In a letter written by Colonel Israel Shreve, a young officer then at Wyoming, to Miss Mima Baldwin, a daughter of one of its prominent families, he speaks of it as “a very pleasant and agreeable village, where they truly enjoy the innocent pleasures of true friends, whose company are more near and dear than all other.” Another interesting epistle which has come down to us from a private, Caleb Miller, who wrote to his mother from Chatham, tells of a longing to hear the Newark church-bells, which, he says, “have a sweeter tone than any he has heard hereabouts,” and hopes the day will soon come when “he can feel the green covering of his native village.” We cannot help wishing that this young man of a religious and somewhat sentimental turn of mind had left us some description of the true Dominie Macwhorter and the Parsonage he knew.

|

During the first part of the war Macwhorter was for a short time the chaplain of General Knox’s army at White Plains. The jovial and good-natured Mrs. Knox, always becoming so devotedly attached to every one she admitted to her friendship, longed for his council arid sympathy at a later period when at Pluckamin. It was there she lost her young daughter, julia,’ whom the elders of the Dutch Church refused a sepulture in their church-yard, considering the fact of the Knoxs being members of the Congregational Church of New England sufficient to warrant their un-Christian-like action.

|

|

The grave of Julia Knox is about twenty-five feet west of the Reformed Dutch Church in Pluckamin. A tombstone is still to be seen bearing the following almost illegible inscription: “Under this stone are deposited the Remains of Julia Knox, an infant who died the second of July, 1779. She was the second daughter of Henry and Lucy Knox, of Boston, in New England.”

|

|

General Knox and many other famous commanders passed nights at the Parsonage when in the vicinity of Newark, and in the low dining-room, where Mrs. Burr used to listen to the laughter of the young Aaron, at a later date, General Washington and Governor Livingston, the “Don Quixote of the Jerseys,” met to talk over affairs of state.

From what can be learned of the Rev. Alexander Macwhorter’s life during the war, his fortunes were at a pretty low ebb, but he obtained his reward after peace was proclaimed, and the great building which his parishioners erected for him on the “home lott” of Robert Treat, the chief founder of Newark, was one of the largest and most beautiful churches in New Jersey. A recent writer says of it: “It stands to-day a noble evidence of the Christian zeal of the good men and women who, nearly a century ago, built it; and it is a grand and appropriately situated monument to the memory of those most worthy and estimable persons who rocked the community in its cradle.”

The Rev. Dr. Macwhorter’s description of his church when first completed has come down to us. He said of it:

Its dimensions are one hundred feet in length, including the steeple, which projects eight feet. The steeple is two hundred and four feet high. Two tiers of windows, five in a tier, are on each side; an elegant large Venetian window is in the rear behind the pulpit, and the whole is furnished in the inside in the most handsome manner in the Doric order.

The good dominie lovingly watched it every day during its erection, and even selected the trees in the Newark woodland to be felled and used for the interior. After it was permanently opened for public worship in January, 1791, never was a parson so busy joining hands in marriage as this brave divine in the succeeding months of spring; and it has been written that he never could leave his home of an evening so many were the happy young couples who rode from distant farms on horseback to have him marry them. To give a list of the people united in the Parsonage afterwards becoming distinguished, one would need to recite a good portion of New Jersey’s history. As the famous historian Mrs. Lamb once wrote of it, “In no other house in New Jersey were so many people made happy or miserable.”

The Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island, and The Central Railroad Terminal

The Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island, and The Central Railroad Terminal

Visit Liberty State Park!